Gauchos in Hollywood: Exoticization and Globalization of Criollismo in the 1920s

Global Convivial Forum

In what ways were a set of contents popularized by criollista literature in Argentina at the turn of the century detached from their literary origins and projected as global export materials by a series of films produced in Hollywood, the centre of world entertainment production, in the 1920s?

Nicolás Suárez (Mecila Junior Fellow 2021)

Throughout the 1920s, Hollywood produced at least fourteen Argentine-themed films, most of which included gaucho characters and were located in the Pampas. Based on these films and the images of the nation that they bring into play, it is possible to explore various strategies through which a repertoire of themes, characters, plots and landscapes promoted by criollista literature were projected globally and then reappropriated by the local culture. This was the subject of my presentation held in the Scientific Colloquium of Mecila’s Research Area Medialities of Conviviality in July 2021, which focused on interdisciplinary research on the production and circulation of knowledge, representations, and imaginaries in contexts of conviviality; that is, relations and exchanges marked by inequalities and difference.

In this framework, understanding criollismo as the group of practices and discourses that create a common feeling of belonging around the figure of the gaucho, the main questions of my research can be formulated as follows: In what ways were a set of contents popularized by criollista literature in Argentina at the turn of the century detached from their literary origins and projected as global export materials by a series of films produced in Hollywood, the centre of world entertainment production, in the 1920s? And how were these productions retransmitted back to the Argentine audience, impacting content production at a local level? Drawing on these crossings between national literature and world cinema, my work is intended as a contribution to the study of the constitutive processes of local cultural identities, and their problematization in global terms.

Rodolfo Valentino in The Four Horseman of the Apocalypse (Rex Ingram, 1921)

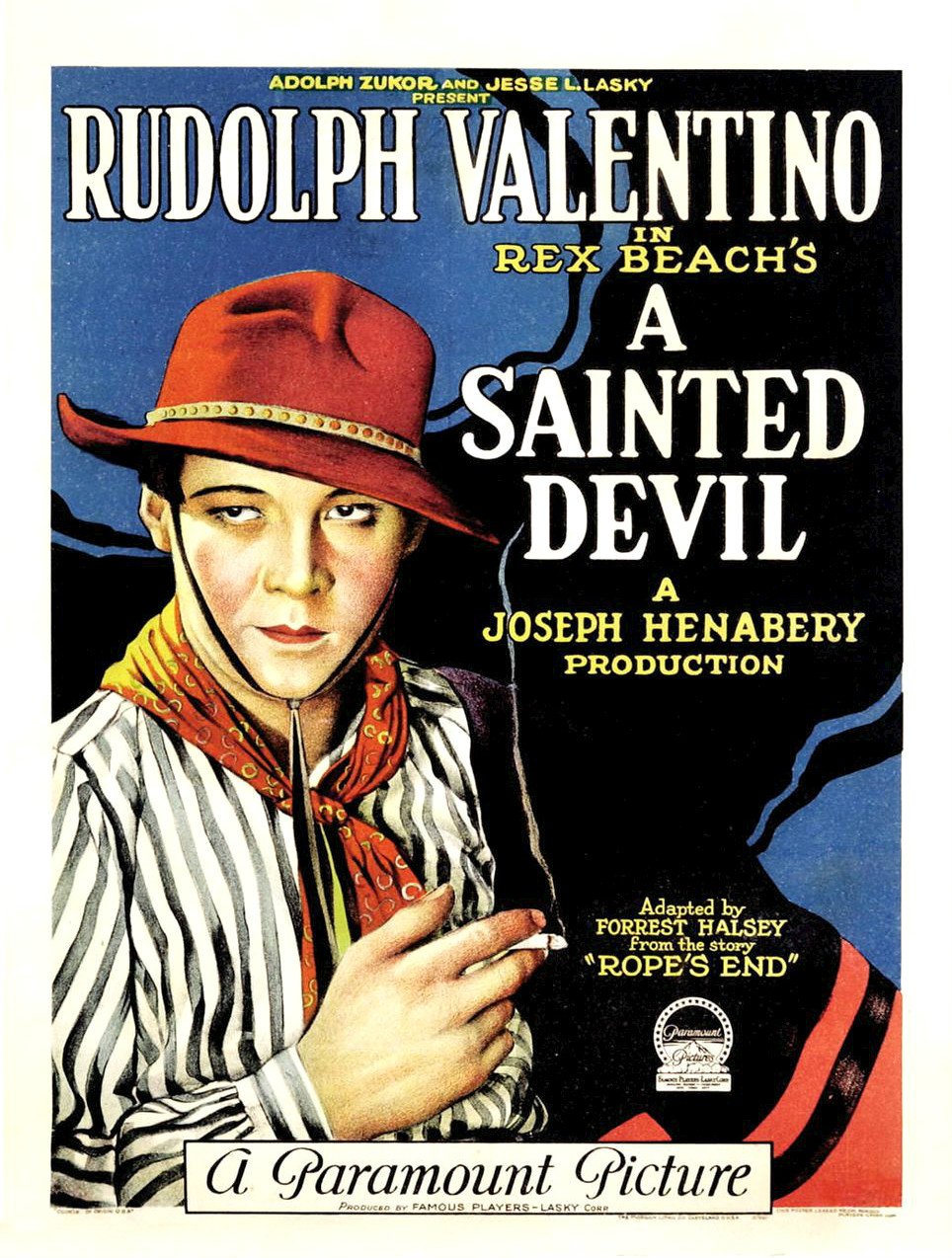

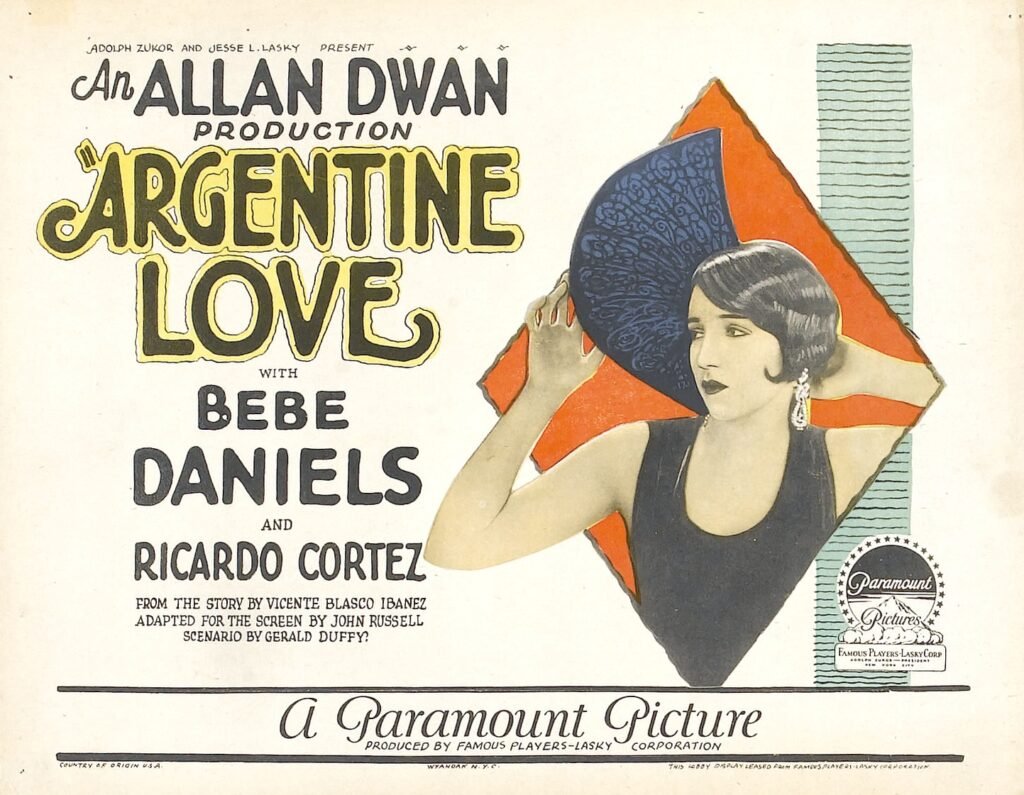

Within the corpus of Argentine-themed films produced in Hollywood during the 1920s, two central cases stand out. On the one hand, there is the famous scene from The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (Rex Ingram, 1921) in which Rodolfo Valentino dances tango dressed as a gaucho and thus initiates an exchange that lasted until the end of the twenties. Based on the anti-war best-seller that the Spaniard Blasco Ibáñez had written in 1916, the film was a worldwide success and established Valentino as an international star. In this sense, the gaucho emblem performs the function of exoticizing Argentine identity as an exportable commodity, and of presenting a type of Latin masculinity that, for the first time, made the female public visible as a differentiated mass phenomenon. Some productions that followed a similar formula are proof of the success of this operation, such as A Sainted Devil (Joseph Henabery, 1924), in which Valentino once again played a gaucho character, or Argentine Love (Allan Dwan, 1924) and The Temptress (Fred Niblo, 1926), both based on stories by Blasco Ibáñez that take place in the Pampas.

On the other hand, Douglas Fairbanks As The Gaucho (Frank Richard Jones, 1927) diverged from these productions, since it involved a type of virile masculinity associated with adventure films. As in Valentino’s case, the appearance of a star like Fairbanks embodying a gaucho character soon prompted new films on the subject, namely The Charge of the Gauchos (Albert Kelley, 1928), an adaptation of Bartolomé Mitre’s Historia de Belgrano (1857), and the animated short film The Gallopin’ Gaucho (Ub Iwerks, 1928), a parody of Fairbanks’ film that showed Mickey Mouse in a gaucho costume. These films are the most prominent examples of a larger corpus of Argentine-themed films produced in Hollywood in the 1920s, including titles such as The Happy Warrior (Stuart Blackton, 1925), Flame of the Argentina (Edward Dillon, 1926), Wind of the Pampas (Arthur Varney, 1927), and Soul of a Gaucho (Henry Otto, 1930).

Thus, from Valentino to Mickey, the stories with Hollywood gauchos cover the generic arc that ranges from the tragedy of the anti-war plight to the caricatured farce. However, at the end of the decade, two situations put an end to this process. From a technical point of view, the arrival of sound film raised linguistic barriers that prevented Hollywood celebrities from playing Latin characters with the same fluency that silent cinema ensured, which negatively affected the global circulation of this kind of films. From a historical perspective, the crash of 1929 and the Argentine military coup of 1930 undermined the optimistic views on the national past and made it increasingly difficult to project onto Argentina the nostalgic images of the Old West as a mythologized time; likewise, for the Argentine imaginary, it was no longer so simple to project a possible or desirable future onto American history.

From that moment on, Hollywood’s forays into themes related to criollista literature would no longer have the success and assiduity achieved in the 1920s. But the traces of this moment of globalization of criollismo would persist in Argentine literature and cinema for a long time, in the form of a presumably spurious gaucho culture that differed from one that intended to be more genuine.

Cover image: Poster from the 1927 movie The Gaucho.

Poster for the 1924 film A Sainted devil

Argentine Love is a lost 1924 Bebe Daniels silent film romance drama directed by Allan Dwan and based on a story by Vicente Blasco Ibanez. This is a contemporary lobby card for the film.