Benjamin Junge (Mecila Senior Fellow / SUNY)

By combining essays on the origins of “whiteness” as a conceptual framework with studies of urban gentrification, and neoliberal capitalism, the sixth volume in the Mecila-CLACSO book series shows us that whiteness in Latin America is simultaneously old and new: It has deep colonial roots yet is constantly reinterpreted in contemporary contexts.

What does it mean to study whiteness in Latin America, and why refer to branquitudes and blanquitudes in the plural? The newest publication in the Biblioteca Mecila series, Branquitudes/Blanquitudes: Diálogos latinoamericanos sobre convivialidad y desigualdad, brings together Latin American scholars to explore these questions. Organized by Mário Augusto Medeiros da Silva, Patricia de Santana Pinho, Roosbelinda Cárdenas, and Hugo Cerón-Anaya, the book is both a collective intervention in whiteness studies and a call for dialogue across languages, regions, and intellectual traditions.

The volume’s editors push against the idea that whiteness is a single, fixed thing, but rather takes diverse, historically specific, and sometimes contradictory forms. The terms “branquitude” and “blanquitud” have emerged in Portuguese and Spanish to name these processes, drawing attention to structural and experiential dimensions of racial privilege. By combining essays on the origins of “whiteness” as a conceptual framework with studies of urban gentrification, and neoliberal capitalism, the volume shows us that whiteness in Latin America is simultaneously old and new: It has deep colonial roots yet is constantly reinterpreted in contemporary contexts.

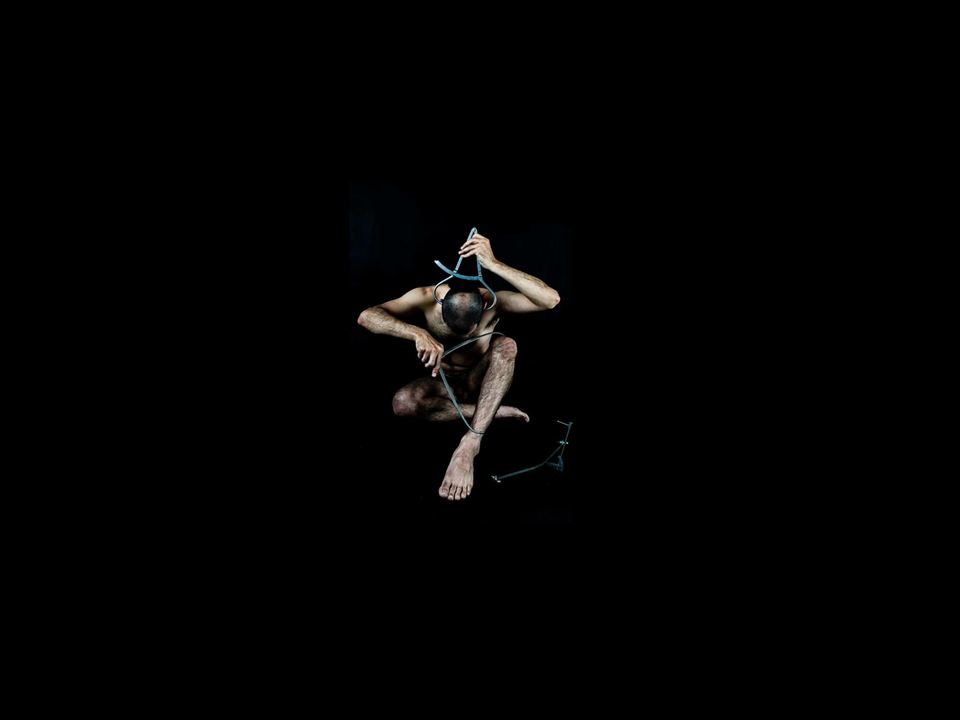

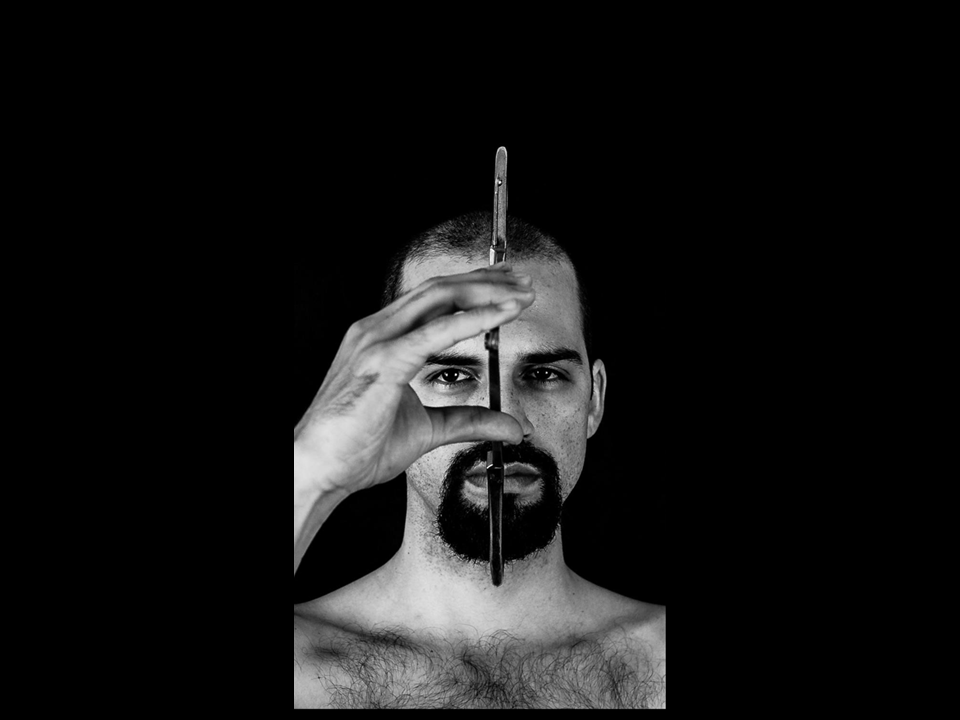

Crédito: Mônica Cardim: Retratos contra a pele.

“Whiteness studies” established itself as a field of study in the United States in the 1990s. But can the conceptual frameworks developed in that context be applied to Latin America and other world areas? From colonial legacies of Iberian rule, to national myths of mestizaje, to the tendency to foreground class and downplay race in sociological analysis, the political, historical, and cultural dimensions of race in Latin America differ significantly. Accordingly, Branquitudes/Blanquitudes positions itself as a regional conversation that both dialogues with and departs from the Anglophone canon. The plural in the title signals something important: There is no singular, objective whiteness to investigate. Rather, the volume’s essays show how whiteness operates differently across time, space, and scale: as ideology, as privilege, as aspiration, and as embodied practice.

Several chapters draw on history to understand how whiteness took root and operated before it acquired a name. Patricia Martins Marcos analyzes Portuguese colonial contexts to argue that whiteness existed long before the concept of “branquitude” emerged. Mário Augusto da Silva shows how Black intellectuals in Brazil from 1945 to 2000 made whiteness visible through critique, even as mainstream scholarship ignored it. Critical thinking about whiteness in Latin America, he shows, didn’t simply appear following the arrival of theory from the global north: it had long been cultivated by Black thinkers themselves. Patricia de Santana Pinho tracks the trajectory of “branquitude” in Brazilian scholarship between 2000 and 2025. Her chapter isn’t only a history of a concept: It gives us a map of an emergent field. She shows how affirmative action debates, the Movimento Negro, and shifting political winds have pushed whiteness studies onto the center stage of Brazilian academia.

Crédito: Mônica Cardim: Retratos contra a pele.

Other chapters reframe and “provincialize” whiteness studies. Verónica Cortés Sánchez shows how scholarly perspectives from Latin America have produced “(re)readings of whiteness.” She asks: What is gained – and what risks are obscured – by the dominance of Anglophone genealogies in the field? Similarly, Cárdena’s chapter proposes the notion of “blanquigrafías hemisféricas” as a method to “write whiteness” across the hemisphere by tracing continuities in racialization, colonization, and capitalism.

The volume’s later chapters bring whiteness into the urgent contemporary moment, focusing on how whiteness reproduces inequality in everyday urban and social life. In her chapter, Ana Y. Ramos-Zayas shows how neoliberal capitalism and whiteness are mutually constitutive, producing not just economic inequality but moral structures for how one is recognized as a “good” citizen, a reliable worker, or a desirable neighbor. Grimaldo-Rodríguez’s chapter addresses gentrification, showing how urban transformation displaces communities of color yet normalizes white spatial dominance. Cerón-Anaya’s chapter argues that whiteness can’t be understood apart from gender and class; hence, the importance of intersectionality not as an “add-on,” but rather a methodology of study in its own right.

Crédito: Mônica Cardim: Retratos contra a pele.

For readers unfamiliar with Latin American debates, Branquitudes/Blanquitudes both shows how whiteness shapes inequality and conviviality in the region. But as importantly, it also carves out space for Latin American scholarship to speak on its own terms. It also signals (and embodies) the importance of interdisciplinary empirical work and theory-building. The volume brings us several major insights. First, whiteness is always relational and it always relies on structures of exclusion and hierarchies of recognition. Second, whiteness is never static, but rather adapts dynamically to neoliberal economies, migratory flows, and shifting cultural imaginaries. Third, whiteness is always also affective, embodied, and aspirational.

As a whole, this important volume invites us to think whiteness differently – to see it not as a ready-made conceptual paradigm borrowed from the North, but rather as a tangle of practices, histories, and power relations that demand closer atention. The stakes here are not merely academic as – in Latin America and beyond – whiteness remains a powerful yet invisible force in everyday life. Branquitudes/Blanquitudes offers us generative perspectives on naming whiteness, studying whiteness, and contesting whiteness – so that more equitable forms of life together become imaginable.