Uma visita ao Museu das Culturas Indígenas de São Paulo: Lembranças, ecos y reflexiones polifónicas

Global Convivial Forum

Flávia Meireles, Berit Callsen, Mariana Simoni

(Mecila Thematic Research Group 2023)

Um lugar físico para a Transformação. Inscrever essa Transformação escrevendo-a na faixa pendurada em uma construção de concreto, mas com isso também deslocá-la, impedir sua rigidez, insinuando que ela pode ocorrer em qualquer ponto daquele espaço limitado – demarcado – do Museu das Culturas Indígenas (MCI) convertido em “Tava” – Casa de Transformação.

Em nossa primeira visita cultural, no dia 22 de junho de 2023, e integrando o grupo de todos os Junior e Senior Fellows do Mecila, nós – Flavia Meireles, Berit Callsen e Mariana Simoni, agrupadas como Thematic Research Group –, estivemos no Museu das Culturas Indígenas, prédio vizinho ao Parque Água Branca, na cidade de São Paulo. Importante mencionar que tal visita estava dentro de uma programação mais extensa, com organização de Roberta Hesse, da short-term visit do intelectual equatoriano do povo Palta Ángel Ramírez, vice-reitor de Pesquisa e Extensão da Universidad Intercultural de las Nacionalidades y Pueblos Indígenas Amawtay Wasi (UINPIAW), em Quito (Equador). Ramírez estava conosco nesta visita como uma das diversas atividades que pudemos fazer juntos durante as duas semanas de sua estadia em São Paulo.

O MCI é, sob a perspectiva originária, chamado de Tava, ou Casa de Transformação, como contaram Cristine Takuá e Carlos Papá, dois dos gestores do Museu, em outra ocasião. Passamos essa tarde sendo guiadas/os pelas mestras/es dos saberes e educadores, que nos apresentaram quem faz e como funciona o MCI, visitando suas exposições atuais e sensibilizando-nos sobre os modos de conhecer/viver indígenas que dão vida aquele espaço.

Vale destacar que a gestão do MCI – que no último dia 29 de junho completou um ano de abertura –, é fruto da conquista dos movimentos indígenas (representados pelo Conselho Indígena Aty Mirim) de fomentar, na cidade de São Paulo, o direito ao território e à educação diferenciada através de uma gestão co-indígena. O MCI é, simultaneamente, lugar de acolhimento para indígenas e meio de educação para não-indígenas sobre – e, principalmente, com – os diferentes povos e cosmologias de Aby Ayala. Essa gestão é sediada em equipamento da Secretaria de Cultura e Economia Criativa do Estado de São Paulo, sob administração compartilhada entre o Instituto Maracá e a ACAM Portinari.

A visita começou com uma grande roda de boas-vindas na parte externa do MCI, em meio às intervenções artísticas nos muros e fachadas do prédio, que já nos envolviam com artes, imagens e grafismos de diversas etnias, dando cor, tom e destaque aos saberes indígenas espraiados por toda parte do imóvel, tornado ninho, refúgio e lugar de trocas indígenas. Também tivemos contato com artesanatos vendidos por indígenas que vêm de muitos territórios e têm no MCI um ponto de apoio para suas vendas.

Adentramos o prédio até o sétimo andar, local onde começou a visita guiada. Fomos descendo os andares e nos deparando com diferentes salas e exposições, que eram ativadas pelos mestres/as dos saberes, enriquecendo nossa experiência sensorial, cognitiva e cosmológica sobre as etnias.

A enorme cobra – cobra grande – localizada nesta sala multiuso, sobre a qual as pessoas visitantes eram convidadas a sentar, além de evocar a imagem da transformação em muitas cosmologias indígenas também provocavam de forma muito concreta a mudança da percepção das visitantes, porque as impelia, ainda que brevemente, a se relacionar com o próprio corpo de maneira diferente.

Ygapó terra firme

“Ygapó, do Tupi Antigo ‘Raízes d´Água’, é um ecossistema formado nas mais antigas regiões geológicas da terra, proveniente de milhões de anos para que a flora resistente pudesse enfrentar as condições de contínuas mudanças e um terreno pobre em nutrientes. […] Ygapó terra firme é a metáfora da resistência indígena, que mesmo em constante ameaça externa vem pela coletividade e compartilhamento de saberes tornar possível o vislumbre de uma futura existência.”

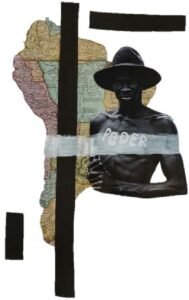

Estas frases se retoman del texto explicativo en la entrada de la segunda sala del museo que alberga una exposición del artista y curador Denilson Baniwa. Al entrar en este espacio llama la atención la oscuridad en él. Las paredes son negras, en ellas relucen escrituras, palabras e imágenes escritas y dibujadas con tiza en diferentes lenguas indígenas y en portugués – noticias, reacciones e impresiones dejadas por los visitantes que son iluminadas por pequeñas lámparas.

La mayor fuente de luz proviene de una pantalla grande en el fondo de la sala, en la que se proyectan diferentes vídeoclips de grupos musicales apropiándose de la cultura pop. Al acercarse a la pantalla, se nota una cuenca con agua en el suelo. El agua no está quieta, sino que se mueve debido a un aporte. Esta es la sala del Ygapó. La superficie líquida y dinámica refleja las imágenes de la pantalla, las multiplica, invierte y modifica. Además, el agua transporta el sonido a su profundidad; se vuelve tanto espejo coalescente como espacio de resonancia haciendo que la sala entera devenga en un ecosistema resistente.

El grupo de rap Oz Guarani canta:

“[…] O índio é forte e sobrevive jogado à própria sorte

O índio é forte e sobrevive jogado à própria sorte

Como pode, sem terra pra morar, sem rio para pescar

O Juruá [não indígena] desmata a mata e mata os M´bya [indígenas]

Mas Wera MC e Oz Guarani

Não cansa de lutar, e seguiremos assim até a morte

O índio é forte […]”

Los/as visitantes-espectadores están buscando su lugar en este espacio del que ya forman parte. Convivir en la diferencia, compartir espacio – en su libro Ideias para adiar o fim do mundo Ailton Krenak lo llama “fricção”, esto es “ser capaz de atrair uns aos outros pelas nossas diferenças, que derivam guiar o nosso roteiro de vida” (Krenak 2020: 33).

La sala del Ygapó cultiva raíces de agua, apela a la capacidad de la convivialidad, invita al diálogo, recordando y haciendo escuchar voces resistentes. En este espacio performativo, las paredes, la pantalla y el agua devienen dispositivos intermédiales de la polifonía.

Pero es el agua como dispositivo fluyente y movido que desprende una mayor dinámica material y una heterogeneidad semántica en este contexto. Así, la cuenca funge no solamente como espejo líquido de la pantalla, sino que, en relación de sinécdoque, puede hacer referencia al acuífero Guarani, una de las más grandes reservas subterráneas de agua dulce del planeta. Localizado en gran parte del territorio brasileiro, el acuífero es amenazado, constantemente, por la acción humana que conduce a la polución del suelo, a la contaminación y a la modificación de la vegetación nativa de la zona. Así, el agua en la sala del Ygapó no solo refleja el canto resistente, sino que lo incorpora y lo adquiere en un gesto de solidaridad existencial. Es este canto líquido que por medio de su materialidad fluida sabe irritar y subvertir también esquemas binarios. La liqui-dación de relaciones dicotómicas como las entre sujeto-objeto, hombre-naturaleza y agua-tierra puede ser uno de sus efectos epistémicos.

No andar seguinte chegamos, sempre guiados pelos mestres/as, a uma sala cujas paredes e teto eram cobertas de barro, dando uma coloração ocre ou de terra vermelha, sob uma penumbra e o chão coberto com ervas e folhas secas, de diferentes odores, perfumando nossa entrada e narinas. A sala, numa primeira vista, parecia um abrigo na floresta. Este espaço também faz parte da exposição “Ygapó – Terra Firme”, do artista Denilson Baniwa e traz para a Tava parte da floresta, dando relevo, cor, dimensão, escuta e olfato à experiência imersiva.

Houve convite para que ficássemos descalços, podendo sentir a textura e o barulho das ervas e folhas secas espalhadas pelo chão, como se entrássemos na mata ou numa casa na floresta, com diferentes cheiros e sons. As solas dos nossos pés eram, então, estimuladas por diferentes texturas e sons estalavam do contato delas com as folhas, anunciando por onde íamos e criando uma ambientação sonora coletiva, já que éramos muitos pés descalços na mesma sala. Isso trazia uma espacialização do som e nos dava pistas de por onde nossos colegas iam pelo espaço, produzindo música com os passos nesse ambiente mata-casa-núcleo expositivo. No centro da sala, parte em penumbra, parte visto, um tronco espesso de árvore estava deitado no chão, sugerindo que o utilizássemos como banco, como parceiro de apoio para nossos corpos, como lugar de descanso. Depois de um tempo circulando pelo espaço, numa coreografia sonora, nos sentamos no tronco ou ao redor dele para ouvir as histórias e causos de Natalício, indígena da etnia Guarani Mbya, morador da Terra Indígena (TI) do Jaraguá.

Transformação no espaço e nos corpos

Nesta casa o fora e o dentro se integram de maneira tão orgânica que por um momento esta distinção parece ficar em suspenso. Por exemplo: “IMAKÃ UG KUHUKÊ” [“Mãe e filha, abrigo para os sonhos em tempos difíceis”], o mural com a imagem de uma mãe e uma bebê onça, da artista pataxó Tamikuã Txihi, que se encontra no pátio do Museu. Aqui a diferença de tamanho entre ambos os animais, mas também a própria posição de seu olhar recíproco – a mãe olha para baixo e a filha olha para cima – já remetem à transformação: o que chama atenção neste mural, além desta simples troca de olhares entre uma onça grande e uma pequena, é o toque entre elas, mais especificamente a ausência de espaço vazio entre seus corpos, que só ocorre no espaço verde entre as pernas dianteiras da onça-mãe. A contiguidade dos desenhos sugere uma continuidade na própria imaginação de quem olha, que automaticamente completa o corpo da onça filhote. Essa integração visual opera destruindo a ideia de tempo que situa a mãe no futuro, uma vez que o corpo da filha de fato não existe autônoma e materialmente sem o corpo da mãe. Ao mesmo tempo, quem olha precisa do corpo da filha para imaginar que o corpo da mãe se encontra no plano de trás, superposto por ele. Em outras palavras: aqui temos uma transformação que se configura simultaneamente no presente, no passado e no futuro. Que se faz ver no espaço. E nos corpos.

Muito mais do que um continente que abarca um conteúdo, um acervo de objetos, este museu parece operar como uma moldura que, antes de mais nada, afirma e inscreve performativamente seu direito de existir na geografia da cidade. Cristine Takuá afirma que o MCI não tem somente acervos, mas sim, pessoas, ressaltando o caráter dinâmico desse espaço como Tava que, a partir da lógica transitória da transformação, se abre para as culturas indígenas em constante movimento, afirmando, portanto, sua própria vida e atualidade.

Krenak, Ailton (2020): Ideias para adiar o fim do mundo, São Paulo: Companhia das Letras.